From Pleasanton Weekly | July 1, 2022 |by Tim Hunt

Spend some time talking with Gatik Trivedi and you will be impressed.

Trivedi just finished up his sophomore year at Dougherty Valley High School in San Ramon, and he’s already developed a diagnostic technology that is designed for widespread use in the undeveloped countries of the world. He’s engaged in discussions with the Zambia Disease Control Center to run a pilot program there. And he’s well-spoken when discussing it.

Trivedi, during the early months of the pandemic, saw the death toll rising and people were losing loved ones. He wanted to do something about it.

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention protocol at the time said people who tested positive should quarantine for 10 days. As Trivedi investigated the data he learned that the disease could be getting worse and people had no reliable way to monitor their body. The oximeters that measure the oxygen saturation in the blood did not tell enough of the story.

As a result, the virus would take its toll, and by the time a person went to the hospital, they would be admitted directly into the intensive care unit. His belief was a device that could monitor more body functions would result in a patient and caregivers knowing the situation was worsening and seeking treatment sooner.

He set out to design, build and program such a device that would monitor lung capacity, body temperature and blood oxygen levels. Devices are already in the marketplace that provide these diagnostics, but — as U.S.-made medical equipment — they are quite expensive.

His goal is to develop a device that is affordable and can be used in developing countries as well as developed countries. So, he built them himself.

The challenge for him was he needed someone to teach him how to build them — the designing and programming was not an issue, but as he said, “I needed to learn how to solder.”

The solution was to reach out to Stephen Dunifer, who builds devices, and ask him to teach him. Dunifer, like Trivedi, is interested in improving health outcomes and using technology to help it.

The first product was built on a piece of cardboard with the three measuring instruments connected with wires. That demonstrated that the concept worked. It’s battery-powered.

He coded an algorithm that combined the readings using multiple parameters to give a measure of overall health. He then tapped into artificial intelligence modeling to predict the direction of the disease in a patient. Along the way, he developed a mobile app.

To design and build the device, he tapped into software, engineering and bio-tech skills — what he needed to learn was the physical how-tos.

Dunifer said, “He’s very good at reading academic papers, looking at the data (and then utilizing it in his projects). He’s very impressive in that area.”

“The goal is to make it as accessible and accurate as possible,” he said.

A next step will be to build another prototype for field testing that can withstand the rigors of daily use and shipping. Assuming the talks in Zambia bear fruit, that will be the site to demonstrate that the device works. Because of United States health privacy regulations, he cannot do the testing here so he’s moving it offshore — which correlates nicely with his goal.

Although he created it for COVID-19, the capabilities make it suitable for monitoring many diseases because it involves multiple organs. His website calls it, “Accessible correlative diagnostic solution for SARS-Cov-2 impacted Multi Organ Dysfunction monitoring product.”

Once the prototype and pilot trials are completed, then physicians can determine how much more broadly to use it.

Meanwhile, Trivedi and Dunifer are working on another version that will expand the sensors to give an even more accurate reading on how a patient is doing.

“The goal is a unit that covers home telemedicine applications,” Dunifer said. “(It) would give a health care support staff an early warning system and an idea what is going on.”

He said they’d thought about including an EKG, but were concerned about the three electrodes. New technology uses high-frequency doppler waves to monitor cardiac and pulmonary functions and does so with a hand-held paddle. They’re designing it for no bodily contact other than the fingertip on the sensor pad.

Trivedi was born in Bakersfield and then moved with his family to Florida. They returned to California and San Ramon a few years ago. He credits his parents, Hiten and Deepti, for being a big help in his success. His dad works in information technology while his mother is an architect.

After collaborating with Dunifer on the prototype, Trivedi entered the Contra Costa County Science Fair and took first place. He described that win as “very encouraging” and it opened the door to the state and international levels. He finished in the Top 7 at California and then third place in the international competition.

“I met some real important people who were fun to talk to,” he said. He also met many liked-minded students committed to STEM education and careers. The event took place online.

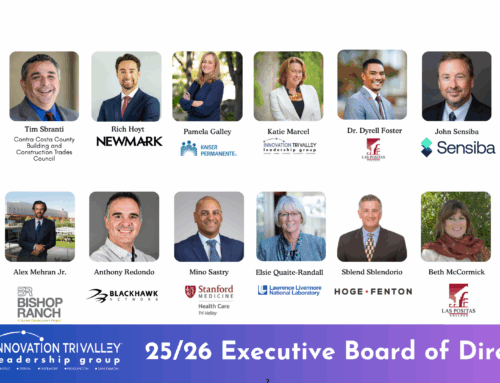

Trivedi was honored by the Innovation Tri-Valley Leadership Group with its Digital Dreamer award this spring.

Over the summer, he plans to finish up his Boy Scout Eagle project — a hay storage structure for starving horses that have been rescued by a Pleasanton-based organization. It will be a busy time for him because he’s also been accepted into a Stanford University summer program on biological pathways and already is working with professors at universities across the country to work on research projects related to biology.

Looking ahead, he plans to attend a university with a strong biological technology program and continue to build his business.

How many high school juniors do you know who have a LinkedIn profile with a link to his innovative startup business, MedTech?

Originally posted here https://pleasantonweekly.com/news/2022/07/01/tri-valley-innovation-monitoring-impacts-on-multiple-organs